Organise! magazine Issue 81 Winter 2013

Download PDF free online: http://www.afed.org.uk/org/org81.pdf

Order online now from AK Press: https://akuk.com/index.php?_a=product&product_id=6982

Order this issue online from Active Distribution: http://www.activedistributionshop.org/shop/magazines/2863-organise-81.html

Order single issues of Organise issue #81 in print by post. Read editorial and links to selected articles below.

Most back issues are also online, and many in print from AK Press or Active Distribution. Search on Organise or Anarchist Federation.

Order last issue (#80) from Active Distribution for £2.00 (while stocks last): http://www.activedistributionshop.org/shop/magazines/2775-organise-magazine-80-summer-2013.html

Please consider subscribing and/or donating to our press fund.

—

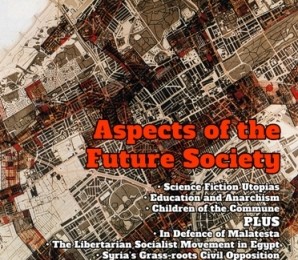

FULL CONTENTS Organise! magazine Issue 81 winter 2013:

- Editorial – What’s in the latest Organise!? Read online below.

Features:

- Utopian? Guilty your honour

- Beyond perfection: What we can learn from science fiction utopias. Read online below.

- Anarchism: Utopian or scientific?

- Children of the Commune

- Education in an anarchist society

- In defence of Malatesta

- Anarchism and organisation

- Syria: The struggle continues

- Statement from the Libertarian Socialist Movement (Egypt)

- Culture Article: Henri Edmond Cross: Painter of Utopia

Reviews:

- “I come to you like the beggar man…” – a review of Ursula Le Guin’s The Dispossessed.

- Carlo Tresca: portrait of a rebel. by Nunzio Pernicone. AK Press.

- Spanish civil war tour, Barcelona (review of walking tour)

Letter:

- John P. Clark’s The Impossible Community: Realising Communitarian Anarchism (Bloomsbury 2013).

Editorial: What’s in the latest Organise!?

It might seem a bit peculiar to have as one of our main themes the idea of Utopia, at a time when the situation both in Britain and around the world seems in many ways to be at its grimmest for many decades. We have seen deteriorating economic conditions as the ruling class and its governments impose massive austerity measures in many countries, we have seen increasing moves to States increasing their repressive powers in response to people daring to fight back against these attacks. We have seen the rise of far-right and anti-immigrant and anti-minority parties throughout Europe. We have seen increasing racism and homophobia, with homosexuality now criminalised in Russia by the Putin regime, coupled with vicious attacks on gay people there by fascist groups.

We have seen the National Health Service under increasing attack in this country, along with plans to privatise Royal Mail. Along with this are further attacks on the unemployed, the imposition of the Bedroom Tax (Poll Tax Mark Two), and massively rising food and energy prices. The increased State surveillance of our mails and phone calls has been revealed and the United States is seen as Spy-Master in Chief, with the British government as a willing accomplice.

The Arab Spring itself, which enthused many, is now turning to an Autumn of Repression; the green shoots of revolt appear to be turning into the brown leaves of repression, with the military regime installed in Egypt. Those old revolutionary hopes that re-emerged in the late nineteen sixties and endured for many decades now seem like foolish fantasies. Yes, that period was a time of great hope, and Utopia was invoked many times, but where are these hopes now, swept away by the greyness of austerity, cuts and the growing power of the police state.

But that is exactly why we have dedicated some of this issue to the idea of Utopia. Even in the grimmest times we need a vision of What Could Be to sustain us. This was the outlook of the revolutionary workers movement when it emerged in the nineteenth century. Anarchists and socialists regularly referred to a future society, where life had been radically transformed. We had works like William Morris’s News from Nowhere, Oscar Wilde’s The Soul of Man Under Socialism, and How We Shall Bring About the Revolution by Pouget and Pataud, as well as The Conquest of Bread and Fields, Factories and Workshops by Kropotkin and Anarchy by Malatesta.

Now all the socialists can offer us is either praise of the market, as with the social-democrat and Labourite parties throughout the world, where it would be difficult to tell the difference between their policies and outlook and those of the Conservative, Republican and Christian-Democrat outfits; and the small Leninist groups, with their vision of a repeat of the fiasco in the Soviet Union, where one repressive and autocratic regime was replaced with another, and which are revealed in their internal practices today- witness the appalling Gerry Healey, as well as the SWP. Only the social, class struggle anarchists still offer the hope of a better world, where there are no wars, no borders, and no inequality, where the fruits of the world are shared in common and prejudice is a thing of the past. That is what should continue to make us fight on, even in grim times. The vision of such a society, a Utopia if you will, should be seen as a lighthouse sending out its beams in the darkness. They must enthuse us to strive for something better, and they must be the inspiring vision of more and more of us as we look for a way out of the social catastrophe that life on this planet now seems. We feel that anarchism can renew itself and once again act as a challenge to the system. As the song Les Anarchistes by the singer Leo Ferré goes, anarchists “Struck so hard, that they can strike again”.

In this issue we talk about the possibilities of what education could look like in a genuine free society basing them on social experiments in education in the past and present. We look at the field of science fiction, a literary form often conducive to showing us a different point of view and of different possibilities. We look at the work of Henri Edmond Cross, one of the French post-impressionist painters enthused by the anarchist idea, who sought to represent this new society on canvas. We reprint Wayne Price’s article on the idea of Utopia itself, where he argues strongly for a re-affirmation of a Utopian outlook.

Also in this issue we look at the ideas and lives of people who fought hard to bring about the birth of this new society. Carlo Tresca was imprisoned and persecuted for his beliefs before ending up being slain by a gunman. Errico Malatesta also suffered many years of persecution, imprisonment and exile, ending up dying under house arrest in Mussolini’s Italy. Neither of them saw this new society, but we hope in the long term that what they dedicated their lives to, what inspired them in extremely difficult situations, can be realised. Indeed it must be realised if we do not want to see a world of barbarism, of the repressive strong state, of war after war, of famine, poverty, and ecological devastation.

We have included examinations of the state of the social movements in Egypt and Syria. Despite the repression of the Assad regime in Syria and the newly installed rule of the Army in Egypt , despite the Islamist threat, despite the strong arm of the police and the Army, despite the carnage and barbarity, we can see that these movements still offer hopes for the future, hopes for the masses in the Middle East and beyond. Remember, the wave of the Arab Spring was unprecedented, and Egypt was seen as an extremely docile and passive place by its neighbours. It took the determined and inspired action of a few, then many, to change this and we saw masses of people on the street there and in neighbouring Tunisia. New social movements attempting to fight the attacks on civil rights, on attacks on pay and conditions, and a whole range of other issues, were to spring up in Turkey, Greece, Brazil and Argentina. This is not the end of the struggle, it is just the beginning.

Did people believe that Louis XVI would be overthrown, that that symbol of ruling class power, the Bastille, would be razed to the ground, even a few days before the revolutionary events of 1789? And yet it happened. Did anyone envisage the end of Charles I before the 1640s? And yet it happened. The fall of the Tsar, the fall of the regimes in Eastern Europe, the fall of Morsi? Great revolutionary movements have emerged and fallen back in the course of the last two centuries, but they all offer us a vision of a new society through their original methods of organisation and their example that power can be challenged. They fell victim to bloody repression and betrayal, but they still endure as to What Can Be.

Recently the government was defeated over its war plans for Syria, with general distaste among the population for such an adventure contributing to this defeat. This was reflected among the general population in the USA and France, and the Allies, at least temporarily, have backed off. What was revealed was the general weakness of the government. This was already there, with the Conservatives, with a minority of votes, maintained in power by their Liberal Democrat allies. Now we see signs of the Liberal Democrats attempting to distance themselves from the Conservatives, in readiness to broker a deal with Labour at the next election. But if the Coalition can be defeated over war plans, surely it can be defeated over the Post Office, over the National Health Service. It only needs the emergence of a mass movement on the streets and in the workplaces to make this come about. We have seen examples of mass movements that were capable of overthrowing regimes emerge around the world. Everywhere the ruling class has been terrified by these developments. It has employed increasingly heavy police measures, not least in Britain, to stop this coming about. Everywhere we have seen the police as brutal and willing servants of the boss class. The union bureaucrats and Labour will attempt to sabotage any such developments, but as we have seen, we need just the conscious will and determination of first fairly small numbers, then many, to give birth to a movement that can stop the Coalition in its tracks.

Finally in this issue, we have republished Malatesta’s article on the need for anarchists to organise effectively. The Anarchist Federation has consistently argued for effective organisation since 1986. We will continue to do so. Anarchists here and abroad must break with their rejection of organisation and develop effective and efficient means of spreading our ideas and examples of libertarian practice. We must involve ourselves in day to day struggles in order to help with the self-confidence of the working class as a whole and to popularise anarchist ideas and practice. as Malatesta has illustrated, this has to be done through the building of a specific anarchist organisation, with effective propaganda, and the growth of mass movements.

—

To order a printed copy see details above.

Organise! magazine, issue 81, Winter 2013.

—

Beyond Perfection: What we can learn from science fiction anarchist Utopias

One of the major criticisms levelled at anarchism as a political philosophy is that it is utopian. Many would argue that this is a misunderstanding of anarchism, that the basis for an anarchist society does not rely on naivety, impracticality or a simplistic and overly positive view of humanity. I want to argue that this is a misunderstanding of utopianism. Of course anarchism is utopian. Anybody who thinks their own ideology is not utopian either hasn’t thought it through properly or, for some reason, wants to live in a society that’s doomed to inequality, misery and eventual self-destruction. And anybody who thinks utopianism is simplistic, impractical or naive clearly hasn’t read enough utopian fiction. There are a plethora of distant worlds that can boast anarchist societies as complex, as pragmatic, as inspired and inspiring, as troubled and as troubling as any historical or contemporary earth-bound revolution, and they all have utopian characteristics.

Then again, those critics may have a point when it comes to some of the 19th Century utopias (e.g. William Morris’ News from Nowhere, H.G. Wells’ A Modern Utopia, Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backward), but as a science fiction reader I have a greater criticism to level against these than their naivety or even their comically dire gender politics: they’re really dull stories. Which isn’t to say they aren’t interesting utopias. As portraits of the utopian ideals of anarchists and socialists of the time, they’re a fascinating insight, and there’s plenty that’s still relevant in their lengthy and technical explanations of the organisation of labour and property. But in terms of plot, character and a sense of place with more depth and veracity than the stage set for a school pantomime, they pretty much fail. Take News from Nowhere, the most anarchist of these early utopias: it’s a guided tour of a pre-industrial pastoral idyll, with no nations or borders, no heavy industry or money, all produce shared freely, all objects beautiful and practical works of artisanship, where the words “work” and “play” mean much the same thing. Fair enough, as holiday brochures go. I’m sold on the week’s stay, but if I’m looking to take up residence in a utopia I generally want to dig a bit deeper and cast a more cynical eye. I might ask questions like: “What happens if the harvest fails?”, “What if a natural disaster requires the speedy need for mass-produced tools and shelters?” and “If child-rearing and home-making are such highly respected, rewarding professions, haven’t any of these sexually free and socially emancipated women ever wondered why there aren’t any men doing them?” There’s something about those unflappably amiable, instant responses the tour guide has to all the protagonist’s questions that suggests a script, or at least a party line, recited by rote and possibly under threat. You want the protagonist to, just once, say something like: “I don’t buy it, beardy. It’s too perfect, and the ‘work is play’ crap sounds distinctly Orwellian to me. Put down the exquisitely carved pipe and tell me where they’re hiding the gulags.”

This might be a little unfair. News from Nowhere was written to explain how an anarchist society can be productive and stable in the conditions of the time and place it was written, not to explore its responses when faced with environmental crisis or massive social change. But you’ve got to admit, answering those questions would make it a much more interesting novel. The utopias that really capture our imaginations are those that are less concerned with the solutions an anarchist society can offer than the problems it might face.

If you’re wondering whether a story exploring problems within an anarchist society is really a utopia, let’s do definitions. The word “Utopia”, coined by Thomas More, comes from a pun on the Greek for “no place” and “good place”. So really, the essential qualities of a utopia are just that there’s something desirable about the society, and that it doesn’t exist. Anybody who thinks that establishing a better society will instantly bring blissful contentment to all is destined to spend the revolution forcibly re-educating dissenters (and until then, they’ll probably be selling you The Socialist Worker). A utopia doesn’t have to be a flawless place, where day to day problems are entirely eliminated. It’s about demonstrating an alternative and preferable way of living. You can do that with a guided tour of a perfect society, but it’s more interesting and more persuasive to show how that society deals with imperfection and conflict, both from within and without.

Iain M. Banks sets his Culture novels in a context that gives his advanced anarchist society something to kick against, namely a universe full of distinctly less utopian societies. The Culture is post-scarcity, high-tech, wish-fulfilment utopianism at its most decadent. Resources are near infinite, labour is unnecessary, and infallible sentient computers (the Minds) with a wry sense of humour and impeccable ethical judgement ensure the smooth running of all environments. The enhanced humanoid residents of The Culture’s many worlds have nothing to fill their near-immortal existences except for games, sex, drugs, the pursuit of intellectual and creative fulfilment, and interference in the development of other societies. This last is the job of an organisation known as Contact, a popular career choice with those who remain strangely unsatisfied by the literally limitless opportunities The Culture has to offer, and take to the stars to see and ultimately save less fortunate worlds. These are the most interesting characters, as their stories tell us most about The Culture itself, and about our own ambivalence towards utopianism. We fear and mistrust perfection even as we strive for it, because it will ultimately leave us with nothing to strive for, no jeopardy to brave, no cause to defend, no meaning to our existence. The Culture, like Nowhere, is a static society, but unlike Morris’ utopia it isn’t merely holding itself in place with a distaste for further development, it has reached the peak of its possibilities – of all possibilities – and has nowhere to go. This is the problem that leads to the restlessness of those who join Contact, and who then struggle with the ethical dilemma of what they do, of whether the worlds they visit even want to be saved, of whether they are, in fact, saving them or dooming them to their own state of existential stasis. It would all be quite angsty if it weren’t for the humour of the Minds, who inhabit armed spaceships that can be as large as planets and give themselves names like Prosthetic Conscience, Of Course I Still Love You, You’ll Thank Me Later, Jaundiced Outlook, Frank Exchange Of Views, Honest Mistake, Zero Gravitas and God Told Me To Do It.

Don’t be fooled by the presence of warships and conflict into thinking this is a trick utopia. There are no false walls here, and the Minds are not secretly megalomaniacal controllers who keep humanity enslaved in luxury for their own ends. They are, themselves, complex and sympathetic (if somewhat ineffable) characters, as caught up in the ethical dilemmas of utopian life as their human companions. While some of them can be manipulative, they seem to be genuinely trying not to be, though they’re so much more intelligent and aware of action and consequence than their organic friends they can hardly help it. The point of this anarchist utopia is not that there’s some ignored power relation at work that compromises its integrity, or even that you can have too much of a good thing. It’s a more subtle and complex message about inertia and entropy, of the nature of power and privilege, and the need for change and development, personal and societal, even in the face of seeming perfection.

At the other end of the scale is Anarres, a scarcity society set on a near-desert moon in Ursula Le Guin’s universe of the Ekumen. It is most fully explored in The Dispossessed, which is subtitled “An Ambiguous Utopia”. Anarres is neither the simple idyll of Morris’ Nowhere nor the paradise of Banks’ Culture. An isolated community, self-exiled from its capitalist neighbour Urras, the Anarresti have built their utopia in far from ideal conditions. This anarchist society suffers famines, labour shortages and social upheavals, and has plenty of technological development still to strive for. Because we see Shevek both growing up on Anarres and explaining his homeworld to those he meets on Urras, there are some good, clear demonstrations of how labour, property, security, family and institutional decision-making work in a world without money or leaders. There are easy parallels to draw with our own world’s revolutions and the founding of Anarres, which reflects the society many Russian revolutionaries envisaged, and might have built if they weren’t trapped in the context of a capitalist economy. Even the language and names sound a little bit Russian. It’s a great utopia for showing how anarchism can build a society as stable as any other system, but also how isolation and ideological orthodoxy breed stagnation, and the importance of revolution as a social value, not a one-off event or a means to an end.

For all these reasons, The Dispossessed tends to be the go-to utopian novel for anarchists trying to explain to the cynical how a society without money or authority could actually work. We see a society in which children are taught from the earliest age that they can’t keep possessions to themselves (though there’s little for them to keep) but are free to do as they choose (and there’s much for them to do.) They learn together through play and discussion, and education continues into adulthood through self-directed research. Work is not compulsory and resources are not rationed, but contribution to the community and distaste for excessive consumption are strong social values. Personal freedom and social duty exist in a balance that is, for the most part, healthy, rational and fulfilling, but this can change with a bad harvest. The story follows Shevek’s career as a physicist whose momentous discovery could affect all the known worlds of the Ekumen. His desire to follow anarchist principles, to avoid propertarianism and unbuild walls, leads him to Urras, which looks a lot like contemporary western democracy (except for those countries that look a lot like contemporary state communism). On Anarres, Shevek battles environmental and social upheavals, informal power structures and the appropriation and censorship of ideas, and yet the anarchist society still manages to come out favourably in comparison with Urras, in which the power structures are even less clear to Shevek, and a great deal more dangerous. Protest and defiance of convention meets with violence on both worlds, but ultimately both have the possibility of revolution, of growth and change, and hope for the future.

Nobody does alternative societies better than Le Guin, and she has created a few besides Anarres that could be viewed as ambiguously anarchist, and more ambiguously utopian. They tend to get less attention than Anarres, probably because they’re less useful for anarchists having arguments. They’re interesting, though, for more subtle discussions of anarchist society and utopianism, ones that explore not the society that anarchists would necessarily wish to build but the many varieties of anarchist society that are possible, the many ways in which human societies could reject hierarchy. One of the most acclaimed is Always Coming Home, but though there is no particular hierarchy of individuals in the societies of the Kesh, there are a great many customs that dictate social status of various kinds, and the reliance on the spiritual and the rejection of technology (aside from some sort of internet that they don’t use much) sends it into a static state. In this way it would resemble News from Nowhere if it weren’t for its much more sophisticated investigation of cultural differences and interactions, and its acknowledgement of various forms of conflict, both personal and societal.

More unusual, and less frequently explored, is the world of Eleven-Soro in the short story Solitude, a world in which a post-cataclysm society has developed social arrangements that go to extreme lengths to guard against the mistakes of the past. Any exercise of power by one person over another is taboo, referred to as “magic”. This includes any attempt to manipulate another’s behaviour, to make them feel guilty or duty-bound to follow a course of action for another’s sake. The men live alone and the women in circles of houses known as “auntrings”, where they educate each other’s children but do not enter one another’s homes and rarely speak to other adult women without good cause, in what seems to be the ultimate expression of anarchist individualism. Nobody asks for or offers help with any task, though women are watchful of one another’s health, send their children with food to the sick and assist each other in childbirth. Only children can ask questions or be taught anything. No adult tells another what to do, or even offers advice except in the most roundabout of ways and the direst of circumstances. Looked at as a society, Eleven-Soro is brutally dystopian (especially for men), but individuals within it can find a kind of utopia that is achieved through the fulfilment of total self-awareness, becoming “a self sufficient to itself”, and in many ways the lives of the Sorovians are rich and happy beyond imagining. It is a strange, sad, beautiful story that consistently challenges gut responses and judgements on the nature of power and community. I highly recommend giving it a read, not as a model for an anarchist society but as a challenge to some of our ideas on interpersonal relationships and social duty.

So which of these societies, if any, comes closest to what we as anarcho-communists aim for? For me, any society claiming utopian status has to be convincingly resilient; show that it’s not going to crumble at the first sign of change or challenge; that its systems are robust enough to undergo cultural, ecological and technological developments without compromising its ideological foundation. Static societies are neither believable nor desirable. Who wants to live in a world where nothing ever changes?

This is the mistake many make about utopianism and about revolution. They think it means embodying an ideal within society and then trying to hold back the tide of human fallibility and outside influence to preserve that moment of perfection. No wonder so many people think it’s a completely unrealistic perspective. That kind of utopianism is not what we strive for, either in life or science fiction. I read utopias and work towards anarchist communism not because I believe in a perfect world but because I believe in a better world. The most inspiring and persuasive utopias are the ones that, like Anarres, don’t just ask, “Where do we want to be?” or even “How will be get there?” but “Where will we go next?” That’s something important for science fiction writers and activists alike to remember. Revolution is not an event but a process, and utopia is a journey, not a destination.

—

To order a printed copy see details above.

Organise! magazine, issue 81, Winter 2013.

—

Social Media